I’m so excited to share that The Storyhouse Writers Showcase has published my article on my trip to Ireland—the land of some of the greatest writers on the planet! Here’s the link, if you’d like to take a look. I’m also posting the article in full below so that I can share pictures!

“I went to Ireland to learn about the writers of the past, but I brought home an experience to share with my students worth so much more. There is a reason Ireland is home to the literary greats. It is an island landscape that fuels the imagination, with a people who burn to tell its stories. In fact, storytelling is such a part of the culture I found in Ireland, that it’s impossible to sort the stories apart from the places and the people.

From the moment we arrived at the Dublin airport we were surrounded by storytellers who loved to spin a good yarn, beginning with the cab driver who took us to the hotel. As we plowed through downtown traffic (a disorienting sight to see whiz by on the “wrong” side of the road), our cabbie kept up a constant stream of banter about the famous buildings, statues, and sights we passed—seamlessly blending history, humor, personal experience, and with even a bit of what I suspect was flat-out fantasy. We were introduced to the “Flirt in the Skirt,” the “Crank on the Bank,” and the ill-conceived and never-ending punchline that is the millennium monument, the “Stiletto in the Ghetto.” As I listened to stories of failed political rebellions, ancient fairy shenanigans, and childhood adventures played along the River Liffey, I began to understand that these writers from the past were born into a culture of storytelling that remains a fundamental way of life for the Irish today.

I began my exploration of Dublin at Trinity College, literary stomping grounds of Jonathan Swift, Bram Stoker, Oscar Wilde, Samuel Beckett, Edmund Burke and so many impressive others. Our true destination waited for us below Trinity’s famous library, where we found the beautifully illuminated Book of Kells—four Gospels of the Christian New Testament, created by Celtic monks. More so than any other site I visited in Ireland, I wished my students were with me in that dimly lit room so they could share the chills I felt when I approached the glass case that houses these golden pages. Raiding Vikings destroyed the cover of the book when they stole its jewels, but monks and the people of Ireland have protected the precious pages that remain since roughly 800 A.D. In today’s age of digital text and transient knowledge, the weight of those 1,200 years can be palpably felt as you stand before the book.

Next, we visited the bog bodies at the National Museum of Ireland-Archaeology, whose incredibly preserved remains have their own terrifying tales to tell. Then it was on to Dublin Castle, where we stopped by the Chester Beatty Library. More ancient texts from around the world waited in darkened rooms, encased in glass. As I wandered through such literary religious history—the earliest copies of the letters of St. Paul, the al-Bawwab Qur’an, Egyptian Books of the Dead, Japanese Buddhist prayer strips—all collected peaceably alongside each other, I was struck by something inspiring among the sacred texts. I left the library feeling comforted in a way that remains difficult to articulate.

After a quick lunch (Irish porridge, which you’d think is oatmeal, but is deliciously not), it was a short walk to Dublin’s Christ Church Cathedral. We paid our respects beneath the gorgeous stained-glass windows, explored the alcoves and tunnels of the crypts beneath the church, then popped across the street to check out Dublinia. At this hands-on museum, we met the Vikings who stole the jewels from the Book of Kells, tried on some Beowulf-like chainmail, and learned how to write our names in Runes, an early Germanic alphabet.

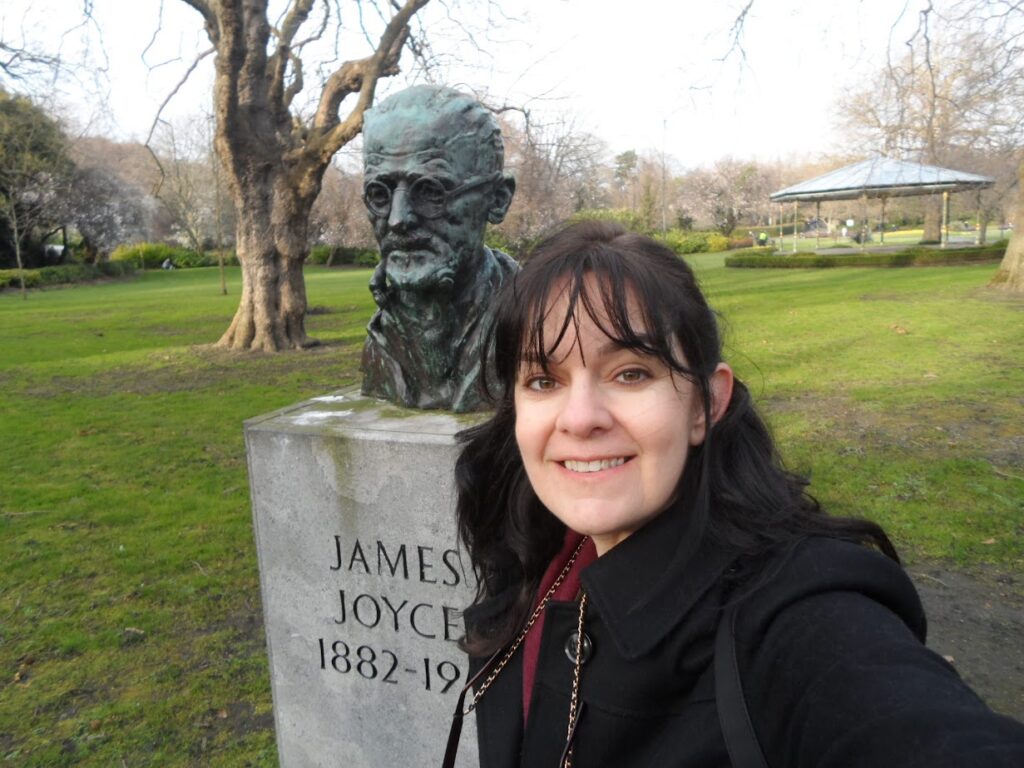

I couldn’t leave Dublin without visiting some of my favorite authors, and I found James Joyce exactly where you might imagine—people-watching in St. Stephen’s Green. As an author with an uncanny understanding of the city of Dublin, his bespectacled monument at the south end of the park is perfectly positioned to keep an eye on the city’s residents. After striking up a conversation with an older Irish woman (who’d caught me taking selfies with Joyce), I learned I’d been looking for Oscar Wilde in the wrong park. She walked me partway to the correct park (Merrion Square) and told me the story of how her late husband’s mother had heard shots fired at the Green during the Easter Rising of 1916. When she asked me if I had Irish blood, I told her I knew only I was part German. She smiled and led us toward the Three Fates Fountain. As we lingered with these women, she told me about “Operation Shamrock,” a beautiful story of the Irish people who had rescued German children during World War II.

From Dublin, we bussed westward across the beautiful countryside (surprisingly green for February!), rented a car in Limerick, toured Bunratty (an authentic medieval castle), stopped for a quick visit in Kiltartan Cross (home of the real-life war hero depicted in Yeats’ “An Irish Airman Foresees His Death”), then landed in a Doolin B&B for the night.

At the recommendation of the proprietor, we walked to O’Connor’s for dinner where we enjoyed an evening of authentic Irish cuisine, craic, which means good conversation, and trad, or traditional Irish music. I was struck by the “band” playing at the pub, in particular. I placed “band” in quotes because the collection of musicians regaling the crowd at O’Connor’s could scarcely be described as such. Throughout the evening various patrons came to sit at the table, drink, eat, and join in with whatever song might be playing, using whatever instruments they brought—accordion, fiddle, clarinet, bodhrán (drum), guitar, flute, even a whistle. The crowd was diverse, from babies in arms, to a frail, wisp of a man who turned his blind eyes to the ceiling and smiled along with the beat. The songs merged one into the next, changing in tone with each instrument added or fallen silent. As I enjoyed my dinner and soaked up the atmosphere, I thought about the collection of musicians that create such a sound. In some ways, I thought, they were similar to the collection of writers that create a movement. I teach the Romantics and the Modernists in my English classroom and each of these writer’s voices blend together to produce a sound specific to their time and place in the world. That night at O’Connor’s, I realized that writer’s words are every bit the instrument of collective expression as these musician’s.

I continued such musings the next day when we visited the Cliffs of Moher. My favorite Irish author, W. B. Yeats once wrote, “Romantic Ireland’s dead and gone,” but as I stood atop a 700-foot cliff and looked over the crashing Atlantic waves, I felt the power of those Romantic ideals thunder beneath my feet. This place where flowing water meets towering, intractable land has been described as a “savage beauty” by visitors and writers alike. It is a wild place, one that can surely make a poet of anyone who experiences it. I felt incredibly isolated, there on the cliff’s edge, braced against a wind that seemed intent on tossing me over. Isolated and terribly, terribly small in the face of a depthless sea, a timeless universe. But even as I felt overwhelmed by such emotion, I also understood I bore witness to the spirituality so many of us find in the glory of nature. It is a place that has drawn millions throughout the millenniums, and even on that cold day in February, there was a crowd of visitors, a cacophony of languages, a friendly sense of community along the cliff edge where we formed a single-file line in what I can only describe as a pilgrimage to the top.

I planned my time in Ireland to include as many literary sites and experiences as possible, but the wonder of travel is that there is always the gift of the unexpected. After my adventure in Ireland, I can now better share what it meant for Beowulf to remove his chainmail prior to his battle with Grendel. I’ve felt the weight of that chainmail myself and can understand on a deeper level how a scop’s (storyteller’s) audience would have felt the vulnerability of that act and connected deeply with such characterization. Having written my name in Runes, I can enhance our discussions on the form and content of communication as we track the evolution of the English language through our course. After experiencing firsthand the joyful revival of Gaelic throughout the island, I will challenge my students to consider how much of their identities are wrapped up in the various languages they use—native, foreign, and via technologies. When we read Joyce’s “Eveline,” I’ll show my students photos of my own walk along the quays by the River Liffey, and I’ll share with them my interactions with the friendly and often surprisingly blunt Dubliners I met during my time there. When I introduce my students to Yeats, I can now speak to the mysticism of the land where he grew up, a land of portal tombs and fairy rings that blends history with folklore and fantasy, and that shaped a Modern writer into a Romantic soul.

After having visited Ireland, I can go back to my classroom and perform the most ancient and sacred duties of a teacher’s calling—the gathering of knowledge and wisdom from the world to bring back to my students so that they might be better prepared when they set out on their own adventures.

On our last day in Ireland, we drove east, back across the island, navigating through the Burren, where we visited the burial site of Poulnabrone Dolmen, and then arrived in Newgrange just in time for the last tour of the day. Nestled in the Boyne River Valley, Newgrange is a Stone Age passage tomb that predates both the Pyramids of Giza and Stonehenge. Based on the tomb’s precise proximity to the winter solstice, archeologists have assumed Newgrange served as a sort of calendar for a people whose entire existence depended on the whim of passing seasons. Over thousands of years, hundreds of communities have used the space for ceremonies and functions, the purpose of which we can only speculate, based on the carvings and items they’ve left behind. The tour allows visitors to crawl through the narrow opening and then stand at the center of the tomb where every December 21st the earth and sun align with a small opening and the darkened chamber is set ablaze with light.

It was a perfect way to end the trip, standing in the center of such human history, thinking about the generations of people who had called this place their own. They’d each left their own mark, played their own instrument. They each added their own story to a collective expression of humanity.”